What follows is an excerpt of the article I co-wrote with

Frances Negrón-Muntaner and published in the most recent issue of the journal

NACLA Report on the Americas. To read the full article

click here.

Reggaeton Nation by Frances Negrón-Muntaner and Raquel Z. Rivera

It was a stunning sight, circa 2003. Onstage at San Juan’s recently renovated Hiram Bithorn Stadium, five-time senator Velda González—former actress, grandmother of 11, and beloved public figure—was doing the unthinkable. Flanked by reggaeton stars Hector and Tito (aka the Bambinos), the senator, sporting tasteful makeup and a sweet, matronly smile, was lightly swinging her hips and tilting her head from side to side to a raucous reggaeton beat.

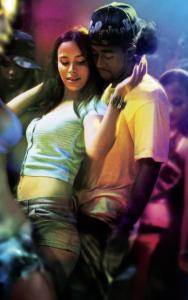

Only a year before, the same senator had led public hearings aimed at regulating reggaeton’s lyrics and the dance moves that accompany it, known as el perreo, or “doggy-style dance,” in which dancers grind against each other to the Jamaican-derived dembow rhythm that serves as reggaeton’s backbone. Using her reputation as a champion of women’s rights, González chastised reggaeton for its “dirty lyrics and videos full of erotic movements where girls dance virtually naked,” and for promoting perreo, which she called a “triggering factor of criminal acts.” Her efforts as reggaeton’s “horsewoman of the apocalypse” touched off such a media frenzy around perreo that Puerto Rican writer Ana Lydia Vega humorously noted the irony of transforming a mere dance into a national obsession. “To perrear or not to perrear,” Vega wrote with characteristic flair. “Finally we have an important dilemma to fill the huge emotional vacuum that we are left with, every four years, by electoral victories and plebiscitary failures.”

Originally dubbed “underground,” among other names, reggaeton is a stew of rap en español and reggae en español, cooked to perfection in the barrios and caseríos of Puerto Rico. Drawing on U.S. hip-hop and Jamaican reggae, Spanish-language rap and reggae developed parallel to each other throughout the 1980s in both Puerto Rico and Panama. Although it was initially produced by and for the island’s urban poor, by the mid-1990s, reggaeton’s explicit sexual lyrics and commentary on the violence of everyday life had caught the ears of a wary middle class that responded to the new sound with its own brand of hostility. “Many people tried to stop us,” recalled Daddy Yankee, reggaeton’s biggest star. “As a pioneer, I think I can talk about that, about how the government tried to stop us, about how people from other social extractions . . . looked down on young people from the barrios, underestimating and seeing us as outcasts.”

Running contrary to middle-class values, reggaeton has been attacked as immoral, as well as artistically deficient, a threat to the social order, apolitical, misogynist, a watered-down version of hip-hop and reggae, the death sentence of salsa, and a music foreign to Puerto Rico. In the exemplary words of the late poet Edwin Reyes, the genre is a “primitive form of musical expression” that transmits “the most elementary forms of emotion” through its “brutalizing and aggressive monotony.”

Faced with an unprecedented and seemingly uncontrollable crime wave, the state also paid close attention to reggaeton. Associated with Puerto Rico’s poorest and blackest citizens, and their presumed disposition toward indiscriminate sexual depravity and violence, reggaeton was targeted by the island government as a dangerous criminal. In 1995, the Vice Control Division of the Puerto Rican police, assisted by the National Guard, took the unprecedented action of confiscating tapes and CDs from music stores, maintaining that the music’s lyrics were obscene and promoted drug use and violence.9 The island’s Department of Education joined in and banned underground music and baggy clothes in an effort to remove the scourge of hip-hop culture from the schools.

But slowly throughout 2003, a campaign year, the body politic began to swing the other way. It became common to see politicians besides Senator González on the campaign trail stiffly dancing reggaeton to show off their hipness and appeal to younger voters. By early 2007, when no one complained after Mexican pop singer Paulina Rubio told the media that her reggaeton single was a tribute to Puerto Rico, since “it is clear that reggaeton belongs to you,” writer Juan Antonio Ramos declared the war against reggaeton officially over.

“Five or seven years ago, such a statement would have been interpreted not only as an unfortunate mistake, but as a monumental insult to the dignity of the Puerto Rican people,” Ramos wrote. “Reggaeton’s success has been such that it no longer has any enemies. . . . It would not be an exaggeration to say that condemning reggaeton has become a sacrilege. It's almost equivalent to being a bad Puerto Rican.”

Though Ramos is overstating the point that reggaeton has no enemies—as recently as August, a local TV personality promised to explore how reggaeton is “fueling the country’s current wave of criminality”—he calls attention to the genre’s trajectory from a feared and marginalized genre rising out of Puerto Rico’s poorest neighborhoods to the island’s primary musical export.11 How could such a dramatic change happen so quickly? How did reggaeton become the dominant sound of the “national” soundtrack? How did a Spanish-language musical phenomenon originating in a poor colonial possession of the United States make it so big that even its former enemies must now pretend to like it?

In a nutshell: commercial success—achieved, however, in the most unexpected of ways.

(To read the full article,

click here.)