For example: “Black” is used as a synonym for African American in the U.S. and, more and more often African Americans and Latinos are spoken about using the language of skin color: “Blacks and Browns.”

But is brown a useful label when so many Latinos are (whether by looks or by ancestry) just as black or even “blacker” than many African Americans? Is brown a useful label to describe Latinos ranging from the milkiest skin-toned to the ebony complexioned?

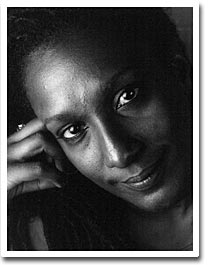

(Below, a great and scary example of racial disparities and myths in Latin America, courtesy of a Colombian travel site.)

The work of photographer Luis M. Salazar, born in El Salvador in 1974, was showcased last year at the S-Files collective exhibit at El Museo del Barrio in East Harlem.

The photo series is titled Spark La Música: Hip Hop en español in New York City, 2003-2005 and features artists like La Bruja, Enemigo, Don Divino, Inti and El Meswy. Considering the huge range of skin tones evident in the photos (from Don Divino and Inti’s deep brown skin to La Bruja’s and El Meswy’s cream-colored complexions) the text accompanying the photos struck me: “They come from [description of their various regional backgrounds]. And besides their color of skin and mother tongue, they all share the love of hip-hop culture.” I wondered: How can the text state these artists share a “color” while the photographic evidence right next to those words screams to the contrary?

“They are the ‘brown’ people,” states the exhibit text, curiously placing “brown” in quotation marks, but still describing their skin color as uniform.

To add yet another spin to the matter, while the above mentioned hip hop artists featured in Salazar’s photo series are from Latin America (Puerto Rico and Colombia), El Meswy is from Spain. So not only is this European artist being incorporated into the definition of Latino, but he is also endowed with the mythical brown-ness of Latinos and Latin Americans. It is a brown-ness that, though using the language of racial phenotypes (looks), stands as a synonym for a Latino pan-ethnicity that reaches across the Atlantic to Spain: to the “motherland” or “evil stepmotherland” of Latin Americans, depending on who you ask.

Some people insist that describing Latinos as brown is appropriate because we are supposedly all mixed. Yet, describing all Latinos as brown is tricky considering some of us are more mixed than others; also considering that some of us are just as mixed as African Americans, Native Americans, Asians or whites in the U.S.; also considering that some of us are not mixed at all; AND, also considering that depending on how mixed you are, you get treated differently, courtesy of Latino and Latin American-style racism and self-hatred.

Other people say that Latino brown-ness is just a convenient label that uses the language of skin color but really points beyond race. They say that brown-ness is a good symbolic way for Latinos to bridge our racial differences. But I do not buy it. This all sounds way too much like Mexican writer Jose Vasconselos’ dangerous myth of the “cosmic race” from back in the 1920s or like 1930s Puerto Rican writer Tomas Blanco playing down Latin American racism as “a kid’s game” compared to racism in the U.S.. Using the label brown to describe all Latinos sounds like a re-packaging of the old myth of “racial democracy” in Latin America.

As long as white is the color of privilege among Latinos and Latin Americans, pretending we are all brown sounds like a terrible idea to me. How can we address racial conflict, differences and inequality among Latinos if, supposedly, we are all brown?